Some products really know how to make an entrance. Originally posted on November 27, 2012.

We’re taught never to judge by appearances. We all do it anyway.

Our all-too-human tendency to judge a book by its cover surely is unfortunate from a social justice standpoint, but from a marketing standpoint it offers an opportunity not to be missed. Namely, the opportunity to dress up your product or service to look the part so that customers will be more likely to buy it, both metaphorically and literally.

Not long ago I had to deal with a clogged drain. Since my otherwise handy sink plunger had proved powerless against this particular clog, I went looking for the meanest, toughest, beefiest industrial strength drain opener I could find. Amid two shelves of brands at The Home Depot, one contender stood out. Its authoritative black bottle certainly impressed, but the coup de grâce was that the bottle was packaged within a resealable plastic bag that was plastered with warnings.

Now, come on. The beefy bottle and childproof cap provided a perfectly safe seal. The bag was nothing more than showmanship. Its sole purpose was to create an impression of contents so dangerously nasty—and, therefore, effective—as to make even the most defiant clog quake with fear.

It worked. I had no choice. I had to buy that brand. Resealable bag and all.

Good showmanship that impresses is part of good marketing. That’s why airline crews dress in crisp, military-style uniforms. You and I both know that attire doesn’t fly a plane, yet most of us would feel less secure if our pilot sported a tank top and cutoffs. It’s why Del Monte makes Milk Bone dog treats in the shape of little, cartoonish femurs. Don’t try telling me that it’s your dog who finds the design charming. It’s why bank presidents wear suits, symphony orchestra players but not rappers don tuxes and formals, the Raid bug killer logo appears in bold, no-nonsense yellow type over a black shield (underscored by a lightning bolt, no less), horror movies have creepy soundtracks, Tropicana sticks a straw in an orange, iPhone packaging evokes an altar, and the Secret brand deodorant logo is set in a script font instead of, say, Stencil or Impact.

Even nature gets in on the showmanship act. As far as anyone can tell, a peacock’s big, colorful tail, a lion’s stately mane, and a gorilla’s elegant silver back — all otherwise useless or even arguable liabilities in the wild — serve to impress.

Regardless of what you bring to market, how you package it matters. Endow your product, store or service with the kind of look and feel—showmanship—that telegraphs “This is the real thing.” You’ll sell more.

Aug 20

10

This time, Congress did its homework before grilling big tech CEOs

“How reassuring it is to know,” I snarked when Facebook tycoon Mark Zuckerberg appeared before the U.S. Senate in 2018, “that powerful people who don’t understand Facebook are investigating Facebook on our behalf.”

Mind you, I appreciate the plight of older congresspeople. They have staff to handle their social media. On one hand, it spares them from having to learn the ins and outs for themselves. On the other, it sets them up to parade their out-of-touchness.

Indeed, during the 2018 fiasco, Senator Lindsey Graham, R, South Carolina, asked Mark Zuckerberg, “Is Twitter the same as what you do?” Senator Bill Nelson, D, Florida, couldn’t figure out why he kept seeing ads for chocolate. And Orrin Hatch, erstwhile senator from my home state of Utah, asked, “How do you sustain a business model in which users don’t pay for your service?” Zuckerberg deadpanned, probably with difficulty, “Senator, we run ads.”

“Hours of withering questions”

But last week, members of Congress appeared a bit savvier. Zuckerberg, along with Apple’s Tim Cook, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, and Google’s (and parent company Alphabet’s) Sundar Pichai, fielded questions before a congressional hearing on anti-trust issues. The questions were better informed, more pointed. As Bloomberg put it, the CEOs endured “hours of withering questions from Congress.”

At times the CEOs, perhaps backed into a corner, seemed to evade. Take, for instance, when Pramila Jayapal, D, Washington, asked Zuckerberg “whether Facebook had ever threatened to squash smaller competitors by copying their products if they wouldn’t let Facebook acquire them.” Kevin Roose of The New York Times wrote:

It was a good question with a clear-cut answer … An honest Mr. Zuckerberg might have replied, “Yes, Congresswoman, like most successful tech companies, we acquire potential competitors all the time, and copy the ones we can’t buy” … Instead, he dodged and weaved …

However, Roose stipulated, “… I don’t mean to pick on Mr. Zuckerberg. Every other witness at Wednesday’s hearing … also dodged lawmakers’ most pointed questions, or professed their ignorance.”

To wit, Politico said that Bezos gave:

… an inconclusive answer on whether the company uses data to undermine its third-party merchants. Amazon is still facing allegations that one of its executives misled Congress about that same issue last year.

Nonentheless, PYMTS.com observed that …

… the consensus view of Bezos’ performance among market watchers is that he was more transparent and authentic than the other CEOs, but also potentially more likely to create issues for his firm down the line thanks to his comments.

As for the other CEOs, Politico had this to say:

Lawmakers hammered Google Sundar Pichai about his company’s relations with China and whether it steals ideas from other businesses, Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg about a blizzard of disinformation plaguing his social network, and Apple CEO Tim Cook on whether his iPhone-maker strong-arms developers on its App Store.

According to technology newsletter Protocol, the CEOs “… answered many questions directly during Wednesday’s antitrust hearing in the House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee. But there were still plenty of questions that the CEOs pledged they’d get to later or declined to answer altogether.”

But the Times, overall, concluded,

… each of the four tech executives appeared to be taken off guard by the rigor and depth of the questions they faced. If they were expecting to teach Tech 101 to a group of clueless lawmakers, they instead found themselves in the principal’s office, being confronted with evidence of the spitballs they’d thrown. And they must have realized, in those moments, that they were seeing the beginnings of accountability.

The outcome was less than ideal, and the topic is far from put to rest.

Protocol further noted that “subcommittee Chairman David Cicilline of Rhode Island ended the hearing by saying that all firms “have monopoly power” and that “the CEOs’ testimony did little to put the issue to bed for Big Tech once and for all.”

Still, the hearing was not without the occasional show of naiveté—or perhaps of ADD—on the part of questioners. That the hearing had been convened to examine antitrust issues did not prevent some lawmakers from venturing into questions of content, fact-checking, and censorship. Here, the poor CEOs couldn’t win. While some representatives scolded them for rejecting certain types of content and products, others scolded them for not rejecting them.

And then there was Jim Jordan, R, Ohio, who asked Cook if “the cancel culture mob” might be “dangerous.”

Remember, these people vote on banking regulations.

What to do with an old bank building?

Originally posted April 8, 2019.

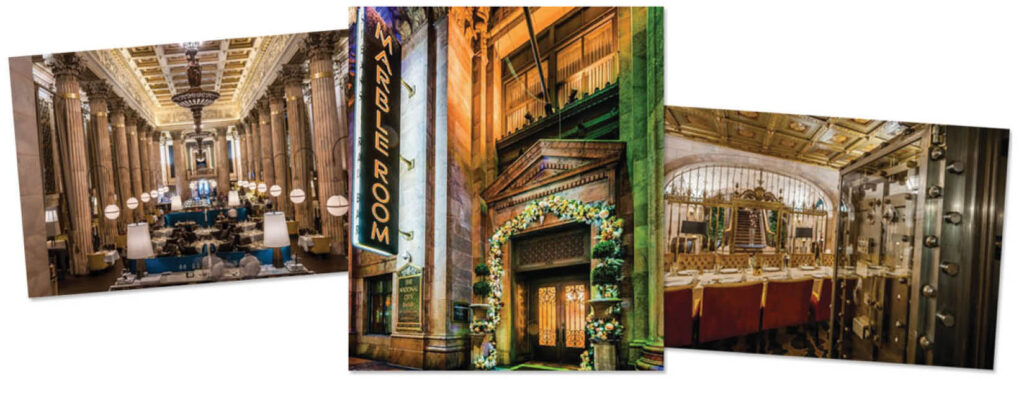

Last week nostalgia swept over me as I stepped inside an architectural masterpiece. An elegant survivor from banking’s bygone era of marble and polished brass, the entire building suggested strength, security, and longevity, all needful symbols for the early 20th century when people weren’t too sure about their banks. I pulled open the massive double doors suspended between towering marble columns, strolled across a checkerboard of brightly polished marble floor tiles, pulled up a chair to a marble-top check-writing stand …

… and ordered from the wine list.

The place was Cleveland’s fabulous, aptly named Marble Room restaurant. It occupies the lobby that once housed National City Bank and, before that, Guardian Savings and Trust. The 126-year-old building, downtown Cleveland’s first steel-frame skyscraper, rose under the direction of Harry Augustus Garfield, son of none other than President Andrew Garfield.

Used without permission. I doubt they’ll mind.

Digital banking fan that I am, even I must admit there is one thing a digital bank cannot do when it moves or ceases operations: It can’t turn into a knock-your-socks-off restaurant.

I have gone on the record as to the continued relevance—for now, anyway—of brick and mortar bank buildings. Still, it’s a fact that branches have closed with the growth of mobile banking. It’s nice to see the buildings not demolished but repurposed.

Vingtage buildings

Vintage bank buildings are a natural fit for restaurants and hotels. In a delightful piece for Bankrate, Mitch Storm lists five bank properties repurposed for the hospitality industry: the Bedford Restaurant (Chicago), CityFlatsHotel (Grand Rapids), Renaissance Denver Downtown City Center Hotel, Bank Brewing Company (Hendricks, MN), and events center Gotham Hall (NYC). Respectively, these buildings now house Home Bank & Trust, Michigan National Bank, Colorado National Bank, Bank of Hedricks, and Greenwich Savings Bank.

Not far from where I live, Salt Lake City’s Continental Bank Building went through a series of financial institution mergers and acquisitions until Kimpton acquired and transformed it into Hotel Monaco. The lobby houses Bambara Restaurant (recommended appetizer: the Blue Cheese House Cut Potato Chips), while the vault houses a bar named, appropriately enough, The Vault.

Classic bank buildings needn’t morph only into upscale restaurants. The restaurant chain that took over an Old National Bank office in Muncie, Indiana, reasoned that to raze the building with its gorgeous canopy would constitute a crime against aesthetics and history. The result is what just might be the most unique Taco Bell you’ll ever see. Not to be outdone, a McDonald’s restaurant has taken up residence in the lobby of Brooklyn’s old Lincoln Savings Bank.

The hospitality industry aside, Storm’s list of repurposed bank buildings also includes: Keystone Trust Co. (Harrisburg), First National Bank (Kansas City), National Bank of Spring City (PA), Bank of Manhattan Trust (NYC), and First National Bank (Columbia, PA). These have yielded their places to, respectively: an art museum, a public library, a private home, a Duane Reade drug store, and an Apple Store. I guess you could sort-of count the Apple Store as a digital bank. But only sort-of.

David Haas, writing for Storycuse, reports that erst bank buildings of Syracuse, New York, house everything from churches to stores. The Central Penn Business Journal points out repurposed bank buildings sporting the likes of petting zoos, bakeries, arcades, video game stores, and an escape room. That last makes uncommon sense: What harder to escape than a bank vault?

You’ll find a Walgreens Pharmacy in an old vault in Chicago. A few years ago, you would have found a porn shop in what began life as New York’s Corn Exchange Bank building. On the flipside and contending for Most Mundane Repurposing Award is a vault in Ventura, California, that now serves as a retail clothing store dressing room.

My nomination for Most Poetic Repurposing Award goes to the space once occupied by Manhattan’s Italian Savings Bank. Today it houses the R.G. Ortiz Funeral Home. I hope the new occupant gave the bank a dignified sendoff.

Aug 20

3

Making old ideas new again for a digital age

A few old ideas are being modernized and revitalized. Among them are installment loans, subscription services, and a close cousin of subscription services known as continuity programs. Part of what’s new about them—and relevant to this blog—is that while such programs were once driven by checks via U.S. Mail, today they are utterly dependent on digital payments.

Installment loans get a new suit of clothes

There’s nothing new, for instance, about installment loans. In fact, “It goes all the way back to the Great Depression and layaway plans,” wrote Fiserv’s Mark Hennin, SVP of Lending and Global Business Solutions, and Brad Goad, VP of Global Digital Commerce. But …

… retailers now are teaming up with Fintechs to enhance digital engagement by allowing consumers to acquire merchandise now and pay for it later. Those installment programs, such as through QuadPay, enable customers to send equal payments over a set period at no interest or additional cost to the buyer.

Although installment payments have found their home in retail, many nontraditional merchants—travel, health care, government and utilities—are adopting the programs to deliver flexibility and convenience. So whether consumers are paying for a car registration, medication or tickets to a sporting event, installment payments are making it easier to acquire goods and services.

In the old days, an installment loan required a customer’s active application. Now, it’s more passive on the customer’s part, with AI payment systems offering installment options at retail and digital points-of-sale. PYMTS.com recently reported that …

… Visa Installments uses Visa application programming interfaces (APIs) and a network of enablers to streamline issuer and seller integration at the seller’s digital POS. Visa Installments turns already approved issuer credit lines into installment payment options at the digital checkout for Visa cardholders.

Subscriptions, too, are making a refurbished comeback.

Subscriptions aren’t new, either. For that matter, neither is refurbishing them. The earliest subscription model applied to periodicals delivered to your mailbox or, in the case of daily newspapers, by paperboys—many of whom were girls—and some of whom were reputed to have the uncanny ability to lob a paper into the only puddle in an otherwise bone-dry driveway.

The concept was later adapted to continuity programs like Columbia Record Club and Book of the Month Club. Each month by mail, members received an “official” selection. They could keep and pay for it, or return it within 30 days and pay nothing. Inertia serves continuity programs well: subscribers often keep and pay for items simply because they don’t get around to returning them. Other kinds of retail products soon capitalized on the idea, such as Seeds of Month, Stamp of the Month, and Panty of the Month.

In our digital age, subscription has even broader application. You can, for instance, “subscribe” to Microsoft Office, Adobe Creative Suite, and Quickbooks instead of purchasing their software outright. You can subscribe to meals via the likes of Freshly and Blue Apron.

The current pandemic has given new life to subscription programs—of which digital payments are in integral part. Another PYMTS.com report states that the subscription model is seen …

… in a whole new light by allowing consumers to get steady supplies of their favorite goods and services direct to their homes without braving store aisles only to find limited inventory. Certain segments of the market have surged, with millions of new subscribers for movie and TV streaming platforms, meal kits and other product boxes.

But then, in other ways the pandemic may be working against subscriptions:

The subscription economy is not immune to the wider economic headwinds, however. Many consumers are wary about their finances, and some feel they are already juggling too many subscriptions. In the current climate, it is more important than ever for subscription businesses to offer flexible plan features — and this includes the ability to temporarily “pause” accounts.

Comic wrinkles

As with any burgeoning field, a few wrinkles remain to be ironed out. Sometimes they can be a bit comic. When a personal acquaintance’s reward points didn’t quite cover his recent online purchase, Visa’s AI immediately offered to let him divide the remainder into four, interest-free monthly payments. He appreciated the gesture, he told me, but in the end he declined Visa’s kind offer, opting instead to bite the bullet and cough up the entire $1.04 balance in one lump sum. “Sometimes,” he said, “I guess, the I in AI isn’t all that I.”

Currency has come a long way since its start in the fourth century BCE. We have arrived at a time and place where you can trade between three and four slips of intaglio-printed paper with the word “One” printed on them for a gallon of gasoline, between one and two thousand of them for a new mattress, tens of thousands of them for a new car, and, in some cases, hundreds of thousands of them for your very own legislator.

There’s something odd about money. Namely, that it has no intrinsic value. What gives it value is billions of people throughout the world agreeing that … well, that it has value.

The Sixth Cents

The total cost in labor and materials for producing one of those slips comes to just under six cents. Larger denominations are slightly more costly to produce because they require more security features. Counterfeiters, it seems, rarely bother with one-dollar bills.

In his book Sapiens: A brief history of mankind, author and historian Yuval Noah Harari refers to the agreed-upon value of money as a “shared myth,” which means pretty much the same thing as “agreed-upon value” but sounds decidedly more scholarly. Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, which contemporary politicians love to cite and, in so doing, reveal that they haven’t read it, describes the value agreement when Francisco d’Anconia responds to the “root of all evil” cliché with a pages-long diatribe. I shall excerpt only a few lines here (you’re welcome):

“When you accept money in payment for your effort, you do so only on the conviction that you will exchange it for the product of the effort of others … Not an ocean of tears nor all the guns in the world can transform those pieces of paper in your wallet into the bread you will need to survive tomorrow. Those pieces of paper, which should have been gold, are a token of honor … Your wallet is your statement of hope that somewhere in the world around you there are men who will not default on that moral principle …”

Rand’s insertion of “…which should have been gold” bears mention. Rand and others who rue the abandonment of the gold standard seem to overlook that gold, too, has a no less tenuous agreed-upon value than printed paper. Its high agreed-upon value is not due to its utility as an electrical conductor but to its coveted position as the stuff of royalty and the rich.

Likewise, diamonds have little intrinsic value yet an abundance of agreed-upon value. For the most part, the only practical uses for diamonds are things like polishing, cutting, and drilling. Diamonds’ popular value is tied to their use in jewelry, a carefully controlled supply, the fairly recent expectation that an engagement ring requires a diamond, and the near elimination of used diamond markets thanks to two sentiments: One, that diamonds are heirlooms not to be sold but kept in the family; and, two, that a “used” diamond is a sign of a stingy, insufficiently smitten prospective groom (even though used diamonds don’t exactly show wear and tear).

So much for gold-backed currency

Though no country has gold-backed currency anymore, currency’s agreed-upon value remains. The danger is that not backing currency with gold leaves a country free to print money at will. Unfortunately, at one time or another most countries have. Rampant overindulgence of the money-printing privilege can be a factor leading to inflation and devaluation. On the other hand, FDR’s letting go of the gold standard helped the United States pull itself out of the Great Depression.

Stocks are the epitome of agreed-upon value. The more people want a stock, the more its price increases—even if the issuing company isn’t doing well. A more recent example of agreed-upon value is cybercurrency. Much like stocks, a cybercurrency’s value depends on how many people are willing to pay for it, and how much they’re willing to pay. The most famous cybercurrency, Bitcoin, needs no introduction, but right now coinmarketcap.com lists 1653 other, actively traded cybercurrencies. How hot are cybercurrencies? Writing for Smithsonian magazine, Clive Thomas cites the case of “… Billy Markus, a programmer who created a joke alt-coin called ‘Dogecoin,’ only to watch in horror as hucksters began actively bidding it up.”

Whether we’re talking dollars, stocks, cybercurrencies, or seashells, the fact remains that an unwritten social contract determines a currency’s value. Yet over the centuries, currency has proven itself a fairly solid house of cards. After all, we still use it. We likely will continue to do so long after we will have replaced paper and coin with ones and zeroes.