Nov 20

26

TBT: Last year’s $7.4 billion Black Friday

If you live in the United States, you may be aware that today is a national holiday known as Thanksgiving. Its purpose is exactly what it sounds like it would be: setting aside time to feel gratitude for … well, for whatever. In the U.S., Thanksgiving falls on the fourth Thursday of November. The next day, “Black Friday,” has traditionally been the biggest retail sales day of the year. But so-called “Cyber Monday” may be turning Black Friday on its head, as this week’s TBT, originally posted last year, suggests. This year, Cyber Monday may be even bigger due the pandemic.

This just in from Associated Press:

This year’s Black Friday was the biggest ever for online sales, as fewer people hit the stores and shoppers rang up $7.4 billion in transactions from their phones, computers and tablets. That’s just behind the $7.9 billion haul of last year’s Cyber Monday, which holds the one-day record for online sales, according to Adobe Analytics … Much of the shopping is happening on people’s phones, which accounted for 39% of all online sales Friday and 61% of online traffic. Shoppers have been looking for “Frozen 2” toys in particular. Other top purchases included sports video games and Apple laptops.

Will Black Friday out-cyber Cyber Monday?

I had set out to write about the origin of the term Cyber Monday—but the truth is there’s no outdoing how Matt Swider and Mark Knapp put it in techradar.com:

As a term, “Cyber Monday” was coined by Ellen Davis and Scott Silverman of the US National Retail Federation and Shop.org, in a deliberate move to promote online shopping back in 2005 when the Internet was made of wood and powered by steam.

Cyber Monday is, of course, a play on Black Friday, which needs no introduction. The latter follows on the heels of Thanksgiving, which in the United States falls officially on the fourth Thursday of November.

For brick-and-mortar retailers, Black Friday marks the biggest shopping day of the year. It is a day of self-punishment during which crowds descend upon stores and malls while complaining about crowds descending upon stores and malls.

I probably don’t need to tell you how Black Friday got its name. You probably know that, as the official start of the holiday shopping season for millions of Americans, it is responsible for nudging many a retailer “into the black.”

As origin stories go, that one for Black Friday makes so much sense, it’s a shame it isn’t true. According to Business Insider, the first use of Black Friday referred to a severe stock market crash:

The term “Black Friday” was first used on Sept. 24, 1869, when two investors, Jay Gould and Jim Fisk, drove up the price of gold and caused a crash that day. The stock market dropped 20% and foreign trade stopped. Farmers suffered a 50% dip in wheat and corn harvest value. In the 1950s, Philadelphia police used the “Black Friday” term to refer to the day between Thanksgiving and the Army-Navy game. Huge crowds of shoppers and tourists went to the city that Friday, and cops had to work long hours to cover the crowds and traffic.

For a while, retailers pushed to change “Black” to “Big.” It never took hold.

According to Adobe Analytics as reported by Wikipedia, in 2006, one year after Swider and Knapp coined the term Cyber Monday, gross sales on that day came to $610 million. Last year, Cyber Monday topped “a record $7.9 billion of online spending which is a 19.3% increase from a year ago.”

To me, the only wonder is that Cyber Monday isn’t even bigger. It is, after all, the ultimate crowd-avoidance opportunity. At the same time, think of the gasoline you won’t burn, traffic accidents you won’t risk, register lines you won’t endure, picked-clean retail shelves you won’t face, the ache that won’t be splitting your head, and sore feet you won’t have to soak when you finally return home, assuming you have time for foot-soaking when you return home.

But then, not every online holiday purchase must be made on precisely that day. The “rush” has already begun, for some as early as late August. And as CNET put it, “there are certainly a zillion Black Friday deals available right now.”

And it’s not as if online shoppers will go into hibernation at sunset tonight. Digital Trends noted, “As with most buying holidays … many of the major sales are probably going to go live even earlier than that and bleed all the way through Cyber Week.” It continues:

You can be sure Cyber Monday will bring great deals on computers, TVs, smart home devices, games and gaming machines, and other tech products. For many, Black Friday is the time to shop for everything, but Cyber Monday is the day to focus on electronics … we expect to see loads of head-shaking deals on 4K HDR TVs, especially for 55-inch to 65-inch models, as well as 70-inch TVs. There will also be tempting deals on soundbars, Nintendo Switches, Amazon Echo, Google Nest, and other smart home devices. Laptops, tablets, and noise-canceling headphones will be highly sought-after and of course, smartwatches including Apple Watches and Samsung wearables. Apple deals for iPhones, iPads, AirPods, and other entertainment options are sure to be on everyone’s list. You can also bet there will be plenty of deals on Instant Pots, coffee makers, and robot vacuums.

To more fully appreciate the mammoth event that Cyber Monday has become, you need only google “Cyber Monday deals 2019.” In fact, permit me to spare you from having to key in all of that: just click here.

As payment options multiply, merge, and grow in capability, you can bet Cyber Monday will only continue to wax bigger and bigger. As one working behind the scenes in the digital payments industry, I hope shoppers will pause to thank us for making possible this respite from the stresses of in-store shopping. But the ironic reality is that the better we all do our jobs—that is, the more seamless and effortless we make digital payment processes—the less shoppers will even know we’re here.

Credit cards are so last-millennium. That is, they were. They’re enjoying a resurgence.

Perhaps you recall, about a year and a half ago, when tech leader Apple executed a seemingly giant, antithetical, technological backward leap with the introduction of its own plastic credit card.*

But why not? Google had already introduced—then withdrew—and now plans to reintroduce—its own debit card. Moreover, reports Finextra, “The Google Pay app has been given a makeover, growing from a simple payments tool to a full-blown financial management service and, from early next year, a gateway to a full bank account.”

Not to be outdone, Venmo, too, has announced a credit card. Venmo promises its card will deliver “a different user experience.” (Ironically, every card promises a different experience—like all the others.) A recent PYMNTS.com article cites Venmo Senior VP Darrell Esch:

The Venmo card will give cash back to customers based on where they actually spend money—categories that can change month to month. “We’re effectively gaming it on the customer’s behalf,” Esch said. “They’ll get the maximum reward for their maximum spend category in any given cycle. It changes with their behavior from cycle to cycle.”

Yet Venmo is arguably late to the party. PayPal introduced its own credit card three years ago. Square launched a debit card at the beginning of 2019. And there is no end to co-branded cards. There’s one for every interest, whether you wish to accrue airline miles, points toward purchases, or support your favorite charity.

Cards go full circle

If I had to summarize the history of credit cards in a single sentence, I might come up with this: They came, it looked like they were fading, and now they’re coming back stronger.

Early charge cards were made from cardboard or metal. I used the word charge on purpose. These were not true credit cards, for they required customers to pay off their balance each month. By the mid 20th century, it seemed as if every substantial business issued its own charge card. The idea wasn’t for issuing merchants to generate interest-generating balances but to create loyalty. The thinking was that customers would be more likely to return to the issuing department store or gas station.

We can thank a forgotten wallet for the first charge card not confined to a single merchant or chain. Chagrined at having dined out only to realize his wallet was still at home, businessperson Frank McNamara introduced the Diner’s Card in 1950. It was a “travel card,” for use within the hospitality industry. American Express introduced its own travel card in 1958.

In time, cardboard and metal charge cards gave way to plastic credit cards. Proprietary cards continued, but “credit card” soon largely referred to two or three major players that had attained near-universal acceptance. By “two or three major players,” I refer to Bank of America with its BankAmericard, later rechristened Visa, and, on its heels, Interbank’s Master Charge, later rechristened MasterCard. These were true credit cards, for they allowed cardholders to carry balances and pay interest. Their use wasn’t limited to a single store, chain, or industry, and it wasn’t long before they were all but universally accepted worldwide. In the 1970s, a store that didn’t accept Visa or Mastercard wasn’t unusual. Within 10 years, it was unthinkable.

Although proprietary cards and credit departments continued, Visa, Mastercard, the later expanded American Express Card came to dominate. In 1985, the Sears Financial Network introduced Discover Card, a would-be threat to Visa and Mastercard. It’s still around, but it never attained equal footing.

For a while in the early 21st-century, it looked as if the rise of digital banking and RFID technology was going to render the “card” in “credit card” quaint if not obsolete. Not so fast. Today, credit cards—physical ones with near-universal acceptance—are coming back in a big way.

And they’re coming from multiple players. Or are they? Mastercard powers PayPal’s, Square’s, and Apple’s cards, and Visa powers Venmo’s card.

Either way, cards yield a wealth of data. Card Expert℠, a product of my employer, Fiserv, provides a great example. According to a Fiserv press release, it …

… aggregates key data and delivers actionable insights in easy-to-use, interactive dashboards, providing financial institutions with the information they need to make critical business decisions about the performance and profitability of their card portfolio … Organizations without a data analyst on staff will appreciate the robust business intelligence capabilities of Card Expert … [it] allows users to type in portfolio questions using natural language to launch powerful custom-data queries … proactively monitors critical key metrics and sends real-time, data-driven alerts; [and provides] instant intelligence on portfolio metrics that are exceeding or underperforming.

The market still seems to appreciate a tangible versus a virtual card, along with the convenience of whipping out a card as opposed to fiddling with an app on a portable device, no matter how convenient.

Cards, it seems, have gone full circle more than once and in more than one way. Chances are they will never disappear.

* Meanwhile, Loup Ventures avers that “Apple Pay is fast becoming a must-have payment option for retailers and banks.”

Nov 20

19

TBT: Banking on Daylight Savings Time

If you live in a part of the U.S. that springs forward and falls back, which is most of the U.S., your body may finally have adjusted to having fallen back 20 days ago. Today’s TBT looks at the effects of biannual time shifts beyond sleep issues. Originally posted on November 11, 2019.

Daylight Savings Time wreaks havoc on everyone, but it brings particular challenges to the banking industry.

I hope you have recovered from this year’s wrapping up of the shock to your system known as Daylight Savings Time.

Seriously. David Gorsky, MD, an oncologist and contributor to the Science Based Medicine blog, did a deep dive into the health effects of DST, resurfacing with a well-documented, not-pretty picture. Here’s what science has been able to document during the few weeks it takes our bodies to adjust to getting up an hour earlier: a measurable increase in traffic-related deaths and pedestrian fatalities (the incidence declines with the return to Standard Time); increased risk of heart attack and stroke; an increase in suicide among men (this also occurs with the switch back to Standard Time); increased human error; and an increase in wasted time on the job.

(And pity the poor clock shop proprietor. Bob Capone, owner of Hands of Time in Savage Hills, Maryland, has the privilege of manually resetting an inventory of some 400 clocks twice per year.)

To be fair, Gorsky points out, DST is also associated with increased physical activity among children and lower robbery rates, both easily attributable to increased daylight hours. But he may be mistaken in allowing that DST may increase retail sales, a belief that helped drive the United States Department of Energy’s 2007 decision to push the cutoff date from October to November. If credit card purchases are an indicator, a JPMorgan Chase study suggests that the increase is illusory. The study tracked credit card purchases in Los Angeles, where DST is observed, and, as control, in Phoenix, where it is not. The study found:

… a 0.9 percent increase in daily card spending per capita in Los Angeles at the beginning of DST and a reduction in daily card spending per capita of 3.5 percent at the end of DST … The magnitude of the spending reductions outweighs increased spending at the beginning of DST.

Ironically enough, the one thing DST doesn’t do is what it was meant to do, that is, cut energy consumption. Depending on whose measure you accept, DST cuts energy use somewhere between 0.03 percent and not at all, or actually increases it.

In financial markets, it appears that moving in and out of DST correlates with riskier investment activity. The University of Glasgow’s Antonios Siganos found that:

… when a merger is announced over a weekend or on a Monday following daylight saving time, the average stock return went up by around 2.50% more in relation to announcements that took place on other days—a statistically significant increase in profits for the target firms.

By way of explanation, Siganos proffers:

With plenty of evidence that investors experience relatively stronger mood swings and higher risk-taking behaviour when their circadian rhythm is disturbed, it seems as though daylight saving time causes investors to push the stock prices of target firms to more extreme values.

It goes without saying that people working in financial services industries are as subject as anyone else to mood, safety, and judgment swings due to time shifts. This can certainly increase human error during acclimatization. Over and above, the banking industry has its technical DST challenges, as this 2007 warning from the FDIC makes clear:

The impact of the DST change may not cause system failures; however, without remediation and preparation, financial institutions could experience automated logging errors, system monitoring difficulties, degraded system performance, or disruption of some services. In addition, malfunctioning systems could result in compliance errors (e.g., incorrect ATM disclosures) and malfunctioning security systems. Examples of other systems that may be affected include those controlling heating, air conditioning, lights, alarms, telephone systems, PDAs (personal digital assistants) and cash vault doors.

An industry with (arguably obsolescent) standards like “close of business” and “working days” already has its hands full with time zones. Regional, national, and international banks need to be mindful that a closed business day in New York will remain in full swing for another five hours in Hawaii. Switching between Standard and Daylight Savings complicates matters further, and locales within the U.S. that opt out of DST, such as Indiana, Hawaii, and certain U.S. territories, complicate them even more. And then there are states like Arizona, where most of the state has opted out of DST, but 27,000 square miles of it—namely, the Navajo Nation—have opted in.

In 1784, Benjamin Franklin wrote that Parisians could conserve candle wax by getting up an hour earlier. But Franklin was joking. He would have been surprised when, a century and a half later, New Zealand entomologist George Vernon Hudson proposed DST in earnest. Germany implemented DST in 1916. The United States followed in 1918 with the passage of the Standard Time Act, better known as the Calder Act.

Not exactly pulling punches, the Financial Post called Daylight Saving Time “dumb, dangerous and costly to companies.” They may have been on to something.

Is delaying the new Bond film’s release an economic predictor?

Eon Productions has once again delayed the release of the newest Bond film, No Time to Die. First the film was going to hit theaters earlier this year in April. Then it was going to debut at Christmastime. Now it’s scheduled for release on a yet-to-be-determined day in 2021.

Accuse me of pedantry, but “yet-to-be-determined” means it isn’t really scheduled at all.

While movie theaters survived radio, TV, and streaming, all predicted to spell the industry’s doom, Covid 19 is a Bond villain the likes of which the industry has never before encountered. Bond fans, it seems, are only figuratively dying to see the next Bond film.

Beyond the fact that this Bond fan’s Inner Walter Mitty must wait a bit longer for the 25th installment in the Bond franchise, the delay may be something of an economic harbinger.

Delaying the release of “Bond 25” is more than a mere matter of making fans wait. Cinemark, AMC, and Regal have shut down. PYMNTS.com put it this way:

“No Time To Die” had been something of a tentpole hope for theater operators looking to recoup some lost ticket sales in 2020 with a film more or less considered a “lock” with loyal Bond fans worldwide. But now, the movie is the latest in a long line of big blockbuster titles that have been bumped to 2021. And while there are a handful of blockbusters—like “Wonder Woman 1984,” “Dune,” and Pixar’s “Soul”—officially still on the calendar for later this year, their status is looking increasingly tenuous as well.

The closures portend job losses, non-performing real estate assets, an overextended Hollywood holding an inventory of already-produced films—and a resultant ripple effect from people working in the industry, from gaffers to concession stand workers who will soon be unable to pay their bills.

All of which will take its toll on the payments business, especially with slow to no sales at sites like Fandango.

Earlier this summer, the movie industry pinned resurgence hopes on Tenet. Yet despite high praise from critics and viewers, Tenet bombed at the box office. It seems there are few people willing to share a theater with potential covid-spreaders, even seated six feet apart.

Direct-to-streaming releases have been moderately successful for films like Disney’s new live-action Mulan, Orion’s Bill and Ted Face the Music, and Amazon Prime’s Borat 2: Subsequent Moviefilm. Even so, the streaming experience for viewers pales in comparison to going to a theater. And the revenues pale as well.

Offbeat predictors

It will not be news to readers of this blog that it takes more than correlation to establish causation. Otherwise, we’d have to concede (speaking of movies) that Nicolas Cage films cause swimming pool deaths, eating cheese increases your likelihood of death by entanglement in bed sheets, and that suicide by hanging, strangulation, and suffocation increases in the U.S.’s spending on science, space and technology. (For these and other hilarious instances of correlation, check out Tiger Vigen’s delightful Spurious Correlations website.)

So, is the movie industry a leading-edge indicator? Maybe. Maybe not. You can quote me on that.

If anyone should know not to confuse correlation with causation, economists should. That doesn’t stop them, however, from seeking the golden fleece in the form of offbeat predictors. Some are better than others. Take, for instance, the Underwear Index, espoused by no less than former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan. Per Investopedia:

The foundational assumption behind this theory is that men tend to view underwear as a necessity instead of a luxury item, meaning that product sales will remain steady, except during severe economic downturns. Critics of this theory suggest that it may be inaccurate for several reasons, including the frequency with which women purchase underwear for men, and an assumed tendency for men not to purchase underwear until it is threadbare regardless of the performance of the economy.

Fatherly put it more simply: “Want to know the economic forecast? Check your underwear.”

There’s something surreal in the thought of prominent economists sitting around debating the portent of underwear sales. But that’s just the beginning. Consider the “Hemline Index.” According to MarketWatch, it is …

… one of the better-known alternative gauges. The index is the brainchild of George Taylor, a professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, who theorized that women’s hemlines rise during economic booms and fall during lean times.

In 2012, Business Insider reported, “This morning, we learned that makeup sales were way up, which scientists believe is a bad sign for the economy.” And then there’s a 2018 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research that said:

… for recent recessions in the United States, the growth rate for conceptions begins to fall several quarters prior to economic decline. Our findings suggest that fertility behavior is more forward-looking and sensitive to changes in short-run expectations about the economy than previously thought.

Not to be overlooked are: the lipstick index (which, according to NPR, covid has pretty well ended), the haircut index (ditto), the Big Mac index, and the dry cleaning index.

None of the above has proved itself a reliable long-term predictor. As for Bond, one sample is hardly enough to draw any sort of firm conclusion. Notwithstanding, the walk-in theater industry is feeling a little shaken, if not stirred.

Marketing had a good deal to do with establishing Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November. With the holiday around the corner, this seems like a good time to revisit the controversy. (Yes, there was one.) Originally posted November 20, 2017.

THE FOURTH THURSDAY of November is a legal holiday in the United States. Designated as a national day of thanks, it is named, appropriately enough, Thanksgiving.

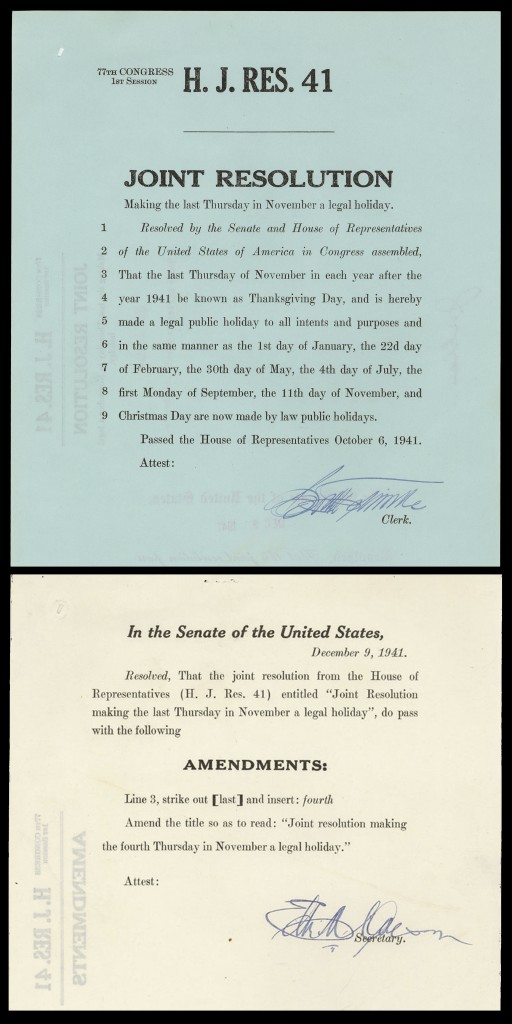

Observing Thanksgiving in autumn has been around since the early 17th century. An act of Congress signed on October 6, 1941 established it as a legal holiday and designated the last Thursday of November as the day.

Which, believe it or not, caused a controversy. Larger merchants argued for establishing the fourth Thursday, fearful that in years in which November had five Thursdays, the last Thursday would leave too little time for Christmas shopping. (This was long before Christmas sales began popping up in September.) Meanwhile, smaller merchants liked the idea of reduced shopping time, hoping to attract shoppers unwilling to put up with too-crowded department stores. Adding to the tumult were not a few citizens who objected to letting commercial concerns move their holiday.

The matter was finally settled two months later, when on December 26, 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed H. J. Res 41. Henceforth the legal holiday would be on the fourth Thursday.

Thanksgiving is a popular time for authors who like debunking tales of “the first Thanksgiving.” True enough, most of the stories we learned in grade school are exaggerated, whitewashed, or outright fabricated. Dig around and you’ll find that the original meal bore no resemblance to today’s feast, and that, overall, the interaction between European immigrants and Native Americans is more to be regretted than celebrated.

History aside, I like the idea of setting aside one day—at least one—to ponder what has gone right for us. Whether we stumble into opportunities or make them, we must at some level concede that something out of our control put us in the right place at the right time, not to mention gave us the wherewithal and skills needed to seize it. Remembering as much can ground.

I do not embrace the cliché that everyone has something to be thankful for. There are many who mourn, and it is not for me to insult them with a pep talk. Nor do I embrace relative gratitude, the idea of feeling blessed because there exist people not as well off. It is not another’s ill fortune that makes mine good. Recognizing that there are less fortunate people serves best when it motivates empathy and compassion.

Now, please pass the gravy.