Dec

21

In a move with serious marketing implications for the financial services industry, Google has revised its targeting policies for housing, employment, and credit.

Here is the latest from Google’s “Advertising Policies Help”:

In an effort to improve inclusivity for users disproportionately affected by societal biases; housing, employment, and credit products or services can no longer be targeted to audiences based on gender, age, parental status, marital status, or ZIP code.

With this policy change, setting aside the tech giant’s irresponsible use of a semicolon, Google is, as The Financial Brand put it,

… throwing a wrench into one of digital marketing’s biggest advantages—targeted ads. The search giant has long had policies in place barring ads targeting consumers based on identity, beliefs or sexuality, but this change drills to the core of what many financial institutions do with their digital campaigns: reach the person most likely to take out a loan or open an account with a highly relevant and timely message.

Google’s action isn’t entirely original. About a year earlier, Facebook arguably laid Google’s groundwork with its own, similarly “staggering” policy change, also reported by TFB.

Sticky wicket

Targeting has long been something of a sticky wicket in advertising. Properly approached, it is at once of benefit to marketers and consumers alike. For consumers, targeting reduces annoying clutter and increases the likelihood of receiving messages of interest. For marketers, as readers of this blog need no reminding, it is the key to crafting a relevant message and knowing where and how to deliver it. The most exquisitely crafted message is doomed to failure if it doesn’t appeal to and arrive in front of front of the right people. Case in point: I recently saw a beautifully executed promotion for a house painting service. It might have been quite successful—if the marketer hadn’t sent it almost exclusively to apartment dwellers.

Consumers voiced concerns about the use of their data long before the digital age. Hoping to preempt regulations, the Direct Mail Association (which later became the Direct Marketing Association, then the Data and Marketing Association, and is now the Association of National Advertisers) created and encouraged consumers to opt on to a national Do Not Mail List, and at the same time urged association members to honor it. But it’s a voluntary system, and consumers remain largely unaware of it, so it has done little assuage concerns.

The information consumers gave up in the old analog days pales in comparison to what they give up—and to what marketers silently capture—in the modern digital age. Name, address, and product choices? That’s kid stuff. If consumers were horrified to learn that ordering a jacket by mail from LL Bean put them on mailing lists available to other marketers, imagine their discomfort if they understood that digital billboards register their smartphones as they drive by, ready to correlate their trip with nearby purchases they may make. Big data is a PR nightmare always at the ready to explode.

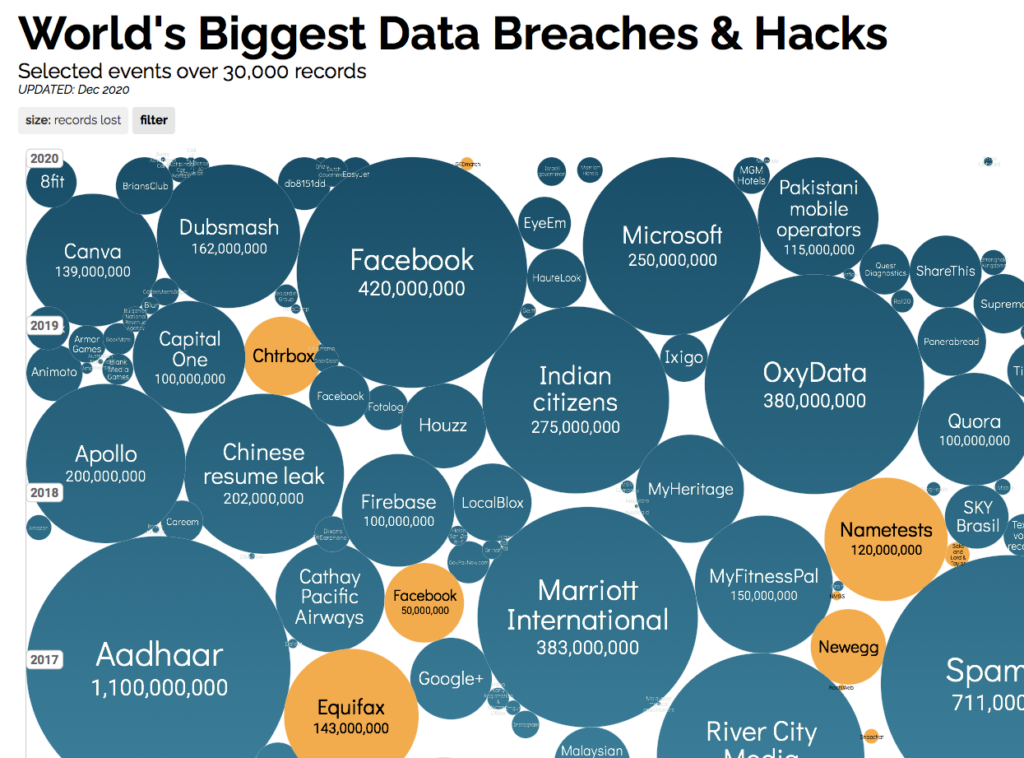

While the distinction between managing masses of data and spying on individuals is generally lost on consumers, marketers’ use of their information is only part of the concern. Consumers also worry about data gleaned by honorable companies only to be hacked by the not-so-honorable. Their concern is not without reason, as this chart from InformationIsBeauitful.net drives home.

Fairness

But let’s return to Google’s stated reason for the policy change: “In an effort to improve inclusivity for users disproportionately affected by societal biases …”

As reasons go, that one has legs. AI is not immune to GIGO. Targeting by gender, age, parental status, marital status, and ZIP code can inadvertently keep scales tilted against traditionally discriminated-against populations, contributing to a downward spiral based on associations and correlations that should have no bearing on what opportunities are extended to whom.

Google’s policy will mean financial marketers will have to work harder. But that’s the thing about fairness. It doesn’t come without work. This policy change isn’t necessarily a bad thing.